A Philosophical and Systemic Inquiry into the Erosion of Empathy and the Doctor–Patient Relationship

Abstract

The progressive erosion of empathy within contemporary medical practice constitutes a critical challenge for global health systems. Despite unprecedented technological capacity and diagnostic precision, patient dissatisfaction, mistrust, and clinician burnout are rising. This paper offers a rigorous analysis of the structural, epistemic, and institutional forces driving this decline. Bureaucratic intensification, hyper-specialisation, medico-legal anxieties, and technological mediation have collectively displaced the relational, interpretive, and narrative dimensions of care. These shifts have reshaped both the phenomenology of the clinical encounter and the epistemology of clinical reasoning.

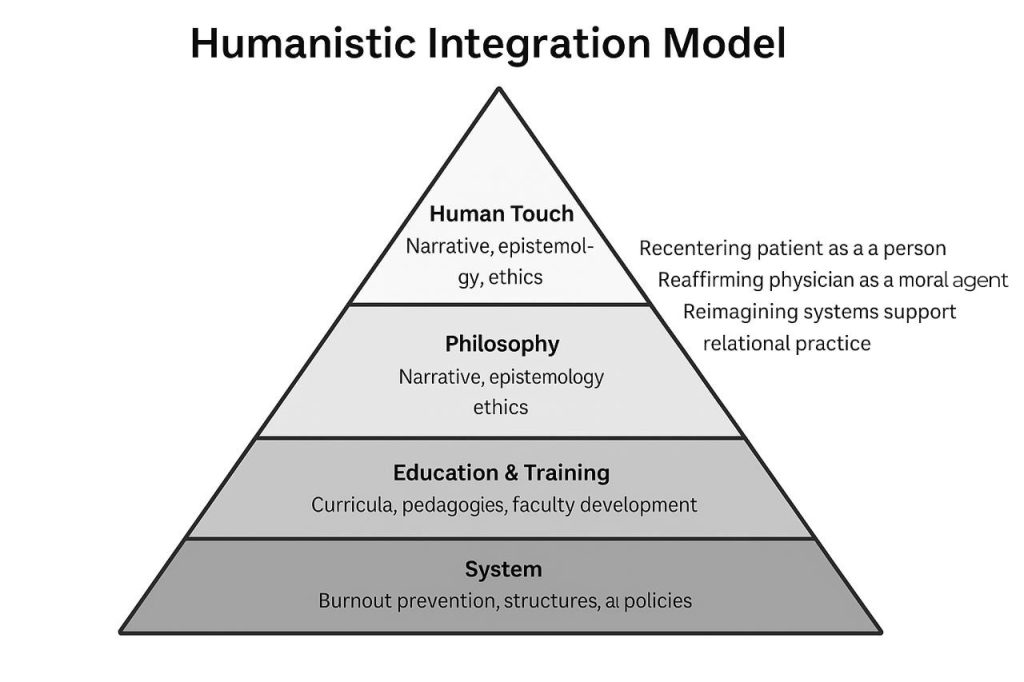

Drawing on empirical literature and medical-education research, this paper proposes a multilayered explanatory framework and a curriculum-integrated, system-supported model for reinstating empathy as a measurable clinical competency. Restoring the human touch requires rebalancing technological sophistication with moral presence, reaffirming the physician as both a moral and epistemic agent, and redesigning systems that enable humane, trustworthy, patient-centred care.

1. Introduction

Modern healthcare exists at a paradoxical moment. While scientific capability has reached unprecedented levels, the experience of clinical care is increasingly characterised by impersonality, fragmentation, and declining trust.¹ Surveys across diverse settings document dissatisfaction regarding communication, continuity, and perceived empathy.². Clinicians simultaneously report escalating burnout, emotional exhaustion, and moral distress.³ These trends are interconnected.

Historically, clinical judgement relied on attentive listening, contextual interpretation, and empathic presence. Today, these skills are overshadowed by administrative and digital demands. Physicians spend more time navigating documentation systems than engaging with patient narratives.⁴

The decline of empathy is not an individual failure but a systemic and epistemic consequence of how modern healthcare is organised.

2. Bureaucratic Intensification and the Reshaping of Clinical Work

The bureaucratic expansion of healthcare has transformed clinical rhythms and priorities.⁵ Regulatory audits, performance metrics, insurance checkpoints, and medico-legal requirements dominate workflow. Defensive documentation—aimed more at risk mitigation than narrative understanding—has become common.⁶

EHR systems reorganise cognitive labour. Physicians spend up to twice as much time interacting with digital interfaces as with patients.⁴ This alters the phenomenology of the clinical encounter: narrative listening is truncated, attention is fragmented, and patient stories are compressed into templated formats.

The epistemic consequence is that biomedical data displaces lived experience as the primary entry point into clinical reasoning.

3. Hyper-specialisation and the Loss of Narrative Coherence

Superspecialisation advances scientific knowledge but fragments patient identity. Organ-based categorisation distributes responsibility across multiple clinicians without guaranteeing narrative integration. Engel’s biopsychosocial model was designed to counter biomedical reductionism⁷, yet implementation remains uneven.

In India, weak primary-care gatekeeping amplifies fragmentation. Patients often consult cardiologists, endocrinologists, neurologists, and orthopaedicians independently, without a clinician who maintains narrative coherence.⁸ Empathy becomes structurally difficult in the absence of continuity.

4. Technological Mediation and the Risk of Dehumanisation

Artificial intelligence and algorithmic decision-support tools are reshaping diagnostic reasoning. These systems emphasise pattern recognition and statistical inference.⁹ While useful, they risk narrowing interpretive space and marginalising contextual and experiential knowledge.

Tacit knowledge—intuition, moral discernment, practical wisdom—cannot be algorithmised. Excessive reliance on computational authority risks reducing clinicians’ interpretive confidence.

Telemedicine, although crucial for access, attenuates non-verbal cues and alters the felt sense of presence.¹⁰ Digital empathy requires explicit competencies—gaze alignment, verbal emotional acknowledgement, structured pauses—yet is rarely taught.

Technology is not inherently dehumanising; dehumanisation occurs when relational counterbalances are absent.

5. Medico-Legal Anxiety and the Transformation of Clinical Morality

Rising litigation and regulatory scrutiny shape clinician behaviour. Defensive medicine—excessive testing, exhaustive documentation, and risk-averse decision-making—has become widespread.⁶ This shifts the moral orientation of care: clinicians increasingly prioritise legal safety over relational engagement.

Moral injury arises when clinicians cannot practise according to their values due to institutional constraints. ¹¹. Emotional distancing becomes a coping mechanism but also diminishes empathy. Patients interpret caution as detachment; clinicians experience scrutiny as a threat.

6. The Patient Experience: Feeling Unseen Despite Technological Precision

Patients frequently report feeling unheard or unseen. Communication analyses show clinicians interrupt patient narratives within 18–20 seconds in most encounters. ¹². Divided attention between patient and screen results in missed cues and incomplete narratives.

Empathy is associated with improved trust, adherence, satisfaction, and clinical outcomes. Diabetic patients treated by higher-empathy physicians demonstrate better glycaemic and lipid control.¹³ Empathy is therefore not sentimental but evidence-based.

TABLE 1. Structural Drivers of Empathy Erosion in Modern Medicine

| Domain | Mechanism | Clinical Impact | Underlying Driver |

| Bureaucracy / EHR Overload | Documentation overshadows dialogue | Fragmented presence | Audit culture |

| Hyper-specialization | Narrative fragmentation | Loss of whole-person view | Subspecialty silos |

| Technology Dependence | Screen displaces relational cues | Reduced attunement | Algorithmic logic |

| Medico-legal Pressure | Defensive practice | Fear-based reasoning | Litigation environment |

| Time Compression | Short consultations | Early interruption | Productivity demands |

| Hidden Curriculum | Normalized detachment | Empathy decline | Hierarchical norms |

7. Restoring Empathy Through Medical Education

Empathy declines consistently during medical training unless intentionally cultivated.¹⁴

A] Curricular Strategies

• Narrative medicine and reflective writing¹⁵

• Shared decision-making pedagogy¹⁶

• Empathy and professionalism-orientated OSCEs¹⁷

• Interprofessional education for holistic reasoning¹⁸

B] Pedagogical Methods

• Observed bedside encounters

• Reflective debriefings

• Ethics and uncertainty case dialogues

• Video-recorded encounter reviews¹⁹

• Telemedicine-specific empathic communication training

c] Faculty Development

Faculty modelling is the strongest predictor of empathy acquisition.²⁰ Institutions must reward humanistic excellence and invest in communication-skills training.

D] System-Level Supports

Empathy becomes sustainable only within supportive systems:

• Documentation-light workflows

• Protected patient-interaction time

• EHR interfaces designed for narrative capture

• Institutional metrics that value patient experience

TABLE 2. Empathy Integration Framework Across Medical Training

| Stage | Strategies | Assessment | Outcome |

| Preclinical | Narrative medicine, humanities | Portfolios | Perspective-taking |

| Clinical | Bedside teaching, reflection | Mini-CEX | Relational competence |

| Residency | Communication under uncertainty | Video review | Advanced empathy |

| CME | Burnout and moral injury modules | Peer review | Sustained empathy |

| System Level | Workflow redesign | Institutional audits | Trust and continuity |

FIGURE 1. Humanistic Integration Model

8. Conclusion

The erosion of empathy in modern medicine is a systemic, epistemic, and institutional phenomenon. Bureaucratic expansion, specialisation-driven fragmentation, technological mediation, and medico-legal anxiety collectively weaken the relational core of care. Restoring empathy requires structural redesign, curricular innovation, and renewed philosophical commitment to medicine as a moral and interpretive practice. Empathy must be preserved as both a clinical competency and a foundational professional virtue.

References

- Blendon RJ, Benson JM, Hero JO. Public trust in physicians—U.S. medicine in international perspective. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(17):1570–1572. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1407373.

- Dugdale DC, Epstein R, Pantilat SZ. Time and the patient–physician relationship. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(S1):34–40.

- Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sinsky C, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2020. Mayo ClinProc. 2022;97(3):491–506. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.11.021.

- Sinsky C, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:753–760.

- Mechanic D. The managed care backlash: perceptions and rhetoric in health care policy and the potential for health care reform. Milbank Q. 2001;79(1):35–54. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00195.

- Studdert DM, Mello MM, Sage WM, et al. Defensive medicine among high-risk specialists. JAMA. 2005;293:2609–2617.

- Engel GL. The need for a new medical model. Science. 1977;196:129–136.

- Patel V, Parikh R, Nandraj S, et al. Assuring health coverage for all in India. Lancet. 2015;386(10011):2422–2435. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00955-1.

- Wong A, Otles E, Donnelly JP, et al. External validation of an AI sepsis prediction tool. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:1065–1070.

- Kruse CS, Krowski N, Rodriguez B, et al. Telehealth and patient satisfaction: a systematic review and narrative analysis. BMJ Open. 2017;7(8):e016242. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016242.

- Dean W, Talbot S, Dean A. Moral injury in healthcare. Fed Pract. 2019;36:400–402.

- Beckman HB, Frankel RM. The effect of physician behavior on the collection of data. Ann Intern Med. 1984;101(5):692–696.

- Hojat M, Louis DZ, Markham FW, et al. Physician empathy and clinical outcomes. Acad Med. 2011;86:359–364.

- Neumann M, Edelhäuser F, TauschelD, et al. Empathy decline in medical school. Acad Med. 2011;86:996–1009.

- Charon R. Narrative Medicine. Oxford University Press; 2006.

- Elwyn G, Frosch DL, Thomson R, et al. Shared decision making. J GenIntern Med. 2012;27:1361–1367.

- Hodges BD, Ginsburg S, Cruess R, et al. Assessment of professionalism: recommendations from the Ottawa 2010 Conference. Med Teach. 2011;33(5):354–363. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.577300.

- Reeves S, Perrier L, Goldman J, et al. Interprofessional education: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes (update). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;3:CD002213. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002213.pub3.

- Norcini J, Burch V. Workplace-based assessment. Med Teach. 2007;29:855–871.

- Branch WT Jr, Kern D, Haidet P, et al. A good clinician and a caring person: longitudinal faculty development and the enhancement of the human dimensions of care. Acad Med. 2009;84(1):117–125. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181900f8a.

Leave a Reply