Knowing, Trust, and Judgement in Modern Clinical Practice

Abstract

Despite unprecedented advances in biomedical science, modern clinical practice continues to struggle with dissatisfaction, non-adherence, diagnostic error, burnout, and moral distress. These failures are often misattributed to gaps in knowledge or technology. This article argues instead that they arise from a deeper erosion of clinical wisdom. Drawing on contemporary medical literature indexed in PubMed, philosophy of medicine, and bedside experience, this essay proposes a unifying framework—the Trilogy of Clinical Wisdom—comprising Knowing, Trust, and Judgement. Each represents an irreducible dimension of medical practice. Knowledge without trust becomes technocratic; trust without knowledge becomes unsafe; both without judgement become mechanistic. Clinical wisdom, the article argues, emerges only when all three operate together in real clinical encounters.

Introduction: Why Medicine Needs Wisdom, Not Just Knowledge

Medicine today is information-rich but often wisdom-poor. Guidelines update faster than most clinicians can read them, diagnostic technologies grow ever more precise, and clinical decision-support systems—including modern artificial intelligence—promise optimisation. Yet the day-to-day experience of practice still includes missed diagnoses, fragmented care, non-adherence, dissatisfaction, and clinician burnout. This mismatch is not merely a technical problem. It reflects a deeper distinction between knowledge and wisdom in healthcare practice: knowledge as the possession of facts and information, and wisdom as the integrated, reflective, and actionable use of knowledge in real human lives.

Recent writing in the medical literature has re-emphasised that clinical progress requires intentional space for wisdom—especially the wisdom carried by lived experience and the relationships that connect wisdom to everyday practice. The point is not to romanticise medicine or diminish science, but to recognise that science alone does not guarantee healing. In a clinical encounter, the translation of evidence into outcomes depends on how clinicians know, how patients trust, and how decisions are judged under uncertainty.

This article proposes a practical framework for clinicians: the Trilogy of Clinical Wisdom—Knowing, Trust, and Judgement. These are not optional virtues or soft add-ons. They are structural pillars of effective care. Each is necessary; none is sufficient alone.

I. Knowing: The Epistemic Pillar

Medical knowledge is provisional, not absolute.

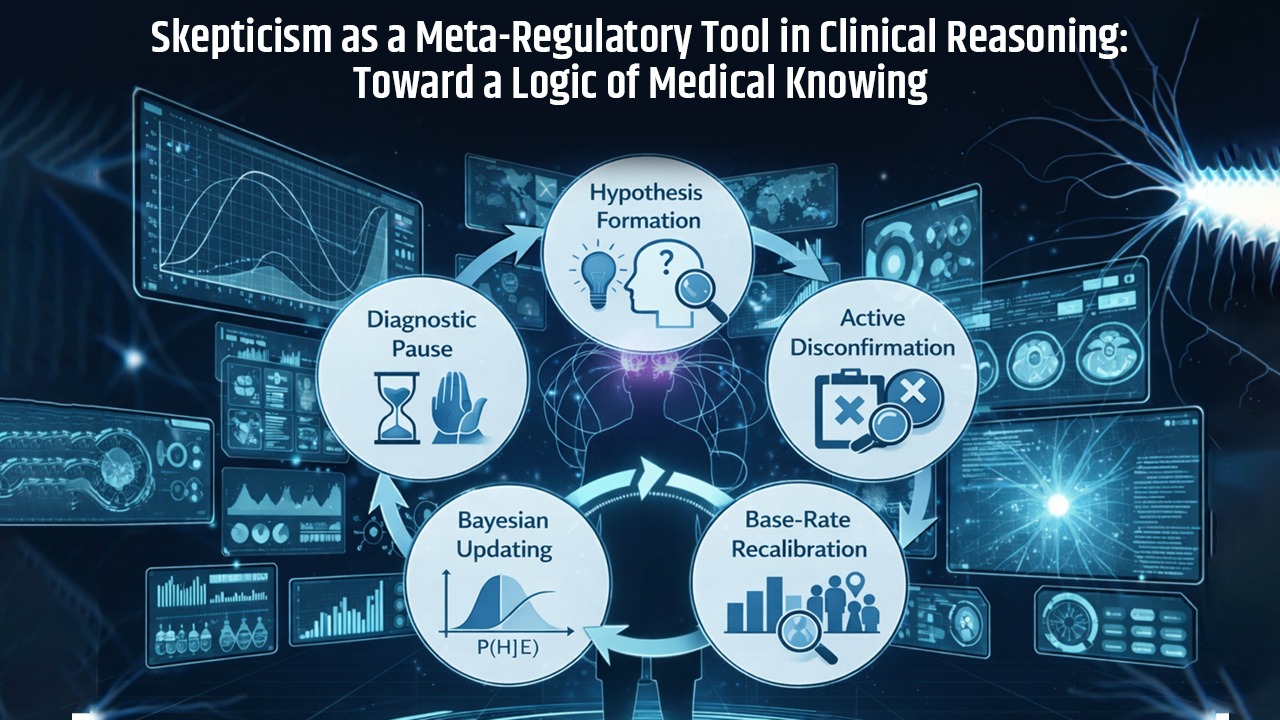

Clinical knowledge differs fundamentally from certainty in mathematics. A diagnosis is typically not a timeless truth but a defensible working hypothesis: the best current explanation of a patient’s presentation, justified by evidence, probability, and clinical reasoning. Evidence-based medicine (EBM) itself was introduced as a method to integrate the best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values, explicitly acknowledging that medical decisions are probabilistic and context-sensitive.

Diagnostic reasoning draws on multiple logics: deduction (applying known rules), induction (learning from patterns across cases), and abduction (inference to the best explanation). Abduction—the disciplined act of selecting the most plausible explanation among alternatives—is the core cognitive move in diagnosis. It is also the point where uncertainty is irreducible: multiple diagnoses can fit the same findings, tests are imperfect, and illness evolves.

Why ‘more data’ does not eliminate error

The persistence of diagnostic error in modern medicine illustrates that uncertainty is not simply a result of insufficient testing. Studies of diagnostic error in internal medicine highlight that cognitive factors—including premature closure and failures to appropriately reconsider hypotheses—play a major role. In other words, a clinician can have access to more information and still arrive at the wrong conclusion if the reasoning process is not deliberately self-correcting.

Overconfidence has been specifically discussed as a contributor to diagnostic error: when clinicians become too certain too early, they stop searching for disconfirming evidence. Epistemic humility—keeping an active space for doubt—functions as a clinical safety mechanism. Wise knowing is therefore not only knowing what is likely but also sustaining awareness of what could still be wrong.

II. Trust: The Relational Pillar

Trust is not ‘soft’; it is clinical infrastructure.

In practice, medical knowledge rarely acts directly on bodies. It acts through relationships. Every plan requires translation into a patient’s behaviour, preferences, fears, resources, and constraints. Trust is the medium that allows clinical knowledge to become clinical action.

A substantial body of work shows that trust in physicians and medical institutions correlates with important outcomes, including adherence, satisfaction, continuity of care, and reduced conflict. When trust is high, patients are more likely to disclose sensitive information, return for follow-up, and accept uncertainty during evaluation. When trust is low, care becomes transactional, fragmented, and adversarial.

How trust is earned (and how it is lost)

Trust is built through reliability and clarity rather than certainty. Patients do not demand omniscience; they seek honesty, attention, and credible commitment. Communication research supports that acknowledging uncertainty—when done transparently and with a plan—does not inherently erode confidence and may strengthen trust by signalling integrity.

Trust is lost when patients experience dismissal, opacity, rushed encounters, or unexplained changes in plans. Systems-level pressures (short visits, fragmented continuity, administrative burden) therefore create an indirect but real clinical risk: they corrode the relational substrate of care.

III. Judgement: The Moral and Practical Pillar

Judgement begins where protocols end.

Clinical judgement is the capacity to act responsibly under uncertainty. Guidelines and algorithms provide population-level guidance, but real patients often fall outside trial criteria: they have comorbidities, atypical presentations, social constraints, and values that cannot be standardised. Judgement is the clinician’s integrative function: weighing probabilities, harms, benefits, timing, and meaning in a particular life.

This is the domain of practical wisdom—phronesis—where knowledge is applied with proportion and moral responsibility. Importantly, judgement is not ‘anti-evidence’; it is evidence ethically and contextually interpreted. The most difficult clinical moments are not those with no information, but those with competing, incomplete, or ambiguous information where multiple paths are defensible.

Judgement carries moral weight.

Judgement also carries moral ownership. Protocols and decision-support tools may inform a plan, but they do not bear the consequence of harm, the burden of explanation, or the memory of regret. This moral dimension is linked to clinician moral distress—experienced when clinicians feel forced to enact actions that conflict with their considered sense of what is right for the patient.

Therefore, protecting and cultivating judgement is not only about better outcomes but also about preserving the integrity of the clinician as a moral agent.

Why the Trilogy is Irreducible

Each pillar is necessary but insufficient alone:

• Knowing without trust becomes technocratic—correct on paper, ineffective in life.

• Trust without knowing becomes unsafe—compassionate but error-prone.

• Knowing plus trust without judgement becomes mechanical—protocol-driven, insensitive to context.

Clinical wisdom emerges at the intersection of all three. This explains why excellent test scores do not guarantee excellent practice, why the most advanced tools do not eliminate error, and why medicine remains irreducibly human even as it becomes technologically augmented.

Implications for Contemporary Practice

1) Evidence-based medicine must be interpreted, not obeyed.

EBM was never meant to replace expertise or values; it was meant to discipline them with the best available evidence. In practice, clinicians must translate evidence into context through judgement and communicate uncertainty through trust.

2) AI can enhance knowing but cannot generate trust or responsibility.

AI systems can recognise patterns and estimate risk. They may improve diagnostic performance in defined tasks. But they cannot form relationships, share moral accountability, or understand a patient’s meaning-making. AI therefore belongs inside the Knowing pillar—while Trust and Judgement remain irreducibly human.

3) Medical education must teach all three pillars explicitly.

Medical training strongly emphasises knowledge acquisition, inconsistently teaches relational competence, and often leaves judgement to be absorbed informally. A wisdom-orientated curriculum would explicitly teach diagnostic humility, relationship-building under time constraints, and judgement under uncertainty, including ethical trade-offs and communication of risk.

Conclusion

Clinical wisdom is not the absence of uncertainty. It is the capacity to act humanely within it. The Trilogy of Clinical Wisdom—Knowing, Trust, and Judgement—offers a practical framework for restoring what modern medicine risks losing: the integrated human competence that makes science therapeutic. As long as unique human beings suffer in unique contexts, medicine will require wise clinicians who can know deeply, relate honestly, and judge responsibly.

Further reading

Dunn KPR, Weasel Moccasin B. Knowledge and wisdom in healthcare practice. Can Liver J. 2024;7(3):383–384. PMID: 40677773.

Guyatt GH, Cairns J, Churchill D, et al. Evidence-based medicine: A new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. JAMA. 1992;268(17):2420–2425. PMID: 1404801.

Graber ML, Franklin N, Gordon R. Diagnostic error in internal medicine. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(13):1493–1499. PMID: 16009864.

Berner ES, Graber ML. Overconfidence as a cause of diagnostic error in medicine. Am J Med. 2008;121(5 Suppl):S2–S23. PMID: 18440350.

Hall MA, Dugan E, Zheng B, Mishra AK. Trust in physicians and medical institutions: what is it, can it be measured, and does it matter? Milbank Q. 2002;80(4):613–639. PMID: 12532603.

Thom DH, et al. Trust in the physician: relationship to patient satisfaction and adherence. J Fam Pract. 2004;53:798–804. PMID: 15455959.

Politi MC, Han PKJ, Col NF. Communicating the uncertainty of harms and benefits of medical interventions. Med Decis Making. 2011;31(5):681–692. PMID: 20667924.

Epstein EG, Hamric AB. Moral distress, moral residue, and the crescendo effect. Hastings Cent Rep. 2009;39(1):28–36. PMID: 19366080.

Montgomery K. How Doctors Think. Discussion indexed in Acad Med. 2006. PMID: 16501296.

Disclaimer: This article is for professional education and reflective practice. It is not intended as individual medical advice.

Leave a Reply