Abstract

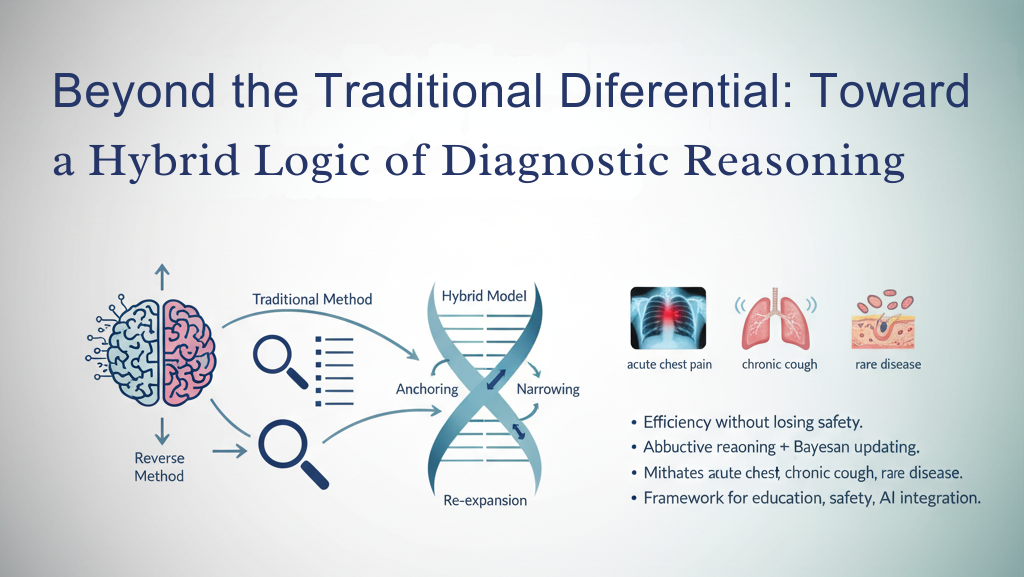

Background: Differential diagnosis has long been the cornerstone of clinical reasoning. The traditional method of exhaustive list-making provides safety but often feels cumbersome in modern practice. Reverse differential reasoning—anchoring on a leading hypothesis and working backward—offers speed but risks error.

Objective: To develop and defend a hybrid model of differential diagnosis that integrates the breadth of the traditional with the focus of the reverse, framed within philosophy, logic, and cognitive psychology.

Methods: Drawing from philosophy of science, clinical epistemology, and cognitive psychology, the hybrid differential is articulated as a four-phase cycle: expansion, anchoring, narrowing, and re-expansion.

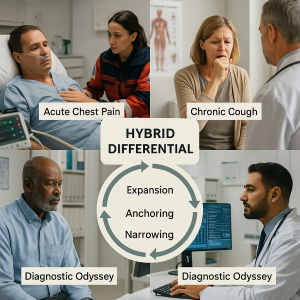

Results: The model provides efficiency without losing safety, integrates abductive reasoning with Bayesian updating, and mitigates cognitive biases. Cases of acute chest pain, chronic cough, and rare disease illustrate its application.

Conclusion: The hybrid differential represents an evolution in diagnostic reasoning—systematic yet pragmatic, humble yet decisive—and provides a framework for education, safety, and the integration of AI into practice.

Part 1. Introduction

To diagnose is to think, to judge, and ultimately to care. Medicine has always been about naming diseases, not as an end but as a bridge between suffering and remedy. The act of diagnosis is not a mere clerical assignment of a code; it is an intellectual achievement and a moral responsibility. When a physician constructs a diagnosis, they do more than identify a pathology. They interpret uncertainty through science, probability, and human judgment.

At the heart of this interpretive act lies the differential diagnosis. Generations of medical students have been taught that to reason clinically is to list all possible explanations for a presentation and then progressively eliminate them. This tradition is more than a pedagogical exercise; it reflects the ethos of medicine itself: never close prematurely, never ignore the rare but catastrophic disease.

Historical Roots: The Oslerian Pedagogy

The differential diagnosis traces its roots to the Oslerian era of bedside medicine. Sir William Osler emphasized the centrality of patient history and careful clinical reasoning. The Flexner Report of 1910, which transformed medical education in North America, further codified the importance of structured diagnostic logic. Students were expected to “give a full differential,” often graded on the length and breadth of their lists.

This model had clear purposes:

• It trained the imagination of the novice physician.

• It instilled humility by reminding them that many diseases can mimic each other.

• It reinforced safety: the rare, catastrophic diagnosis must never be forgotten.

In this sense, the differential diagnosis was not only an intellectual tool but also a moral safeguard. To make a differential was to commit to thoroughness.

The Crisis of the 21st Century

Fast forward a century. The realities of modern practice strain the traditional differential. Consider the emergency physician facing a crashing patient. They cannot pause to recite a dozen causes of chest pain; they must act within minutes. Consider the internist managing an elderly patient with diabetes, hypertension, COPD, and chronic kidney disease.

Generating an exhaustive list of differentials for every symptom becomes a Sisyphean task. Or consider the general practitioner overwhelmed by data from electronic health records, guidelines, and decision-support systems. In such contexts, exhaustive list-making becomes less practical and more paralyzing.

The crisis, then, is not of principle but of practicality. The traditional differential promises safety but risks inefficiency, cognitive overload, and over-testing.

The Reverse Differential Emerges

In response, a contrasting model has taken hold: the reverse differential. Instead of starting with breadth, clinicians begin with the most likely or most dangerous diagnosis—”assume myocardial infarction until proven otherwise“—and work backward, ruling out alternatives.

This model has intuitive appeal. It reflects how many experienced physicians actually practice: focused, decisive, and guided by pattern recognition and clinical urgency. It prioritizes action over completeness. But it has vulnerabilities: anchoring bias, where the first idea dominates judgment, and premature closure, where alternatives are dismissed too soon.

Thus we face a tension. The traditional differential preserves safety but risks inefficiency. The reverse differential preserves efficiency but risks error. Both contain truths; both contain dangers.

The Philosophical Dilemma

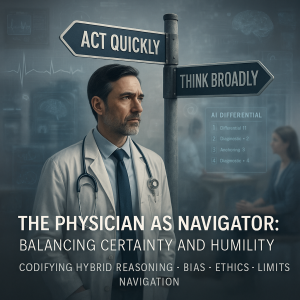

This tension is not just practical but philosophical. It reflects the perennial problem of human reasoning under uncertainty. Should we think broadly, risking paralysis by analysis? Or should we think narrowly, risking error by haste? This is not unlike Aristotle’s idea of the golden mean: virtue lies between extremes. Too much caution becomes indecision; too much decisiveness becomes recklessness.

The philosopher of science Charles Sanders Peirce described abduction—inference to the best explanation—as central to reasoning under uncertainty. Diagnosis is precisely this: generating the most plausible explanation for signs and symptoms. But abduction must always be provisional, open to revision. The danger lies in mistaking provisional hypotheses for certainty.

The modern physician is thus a navigator of epistemic tension. They must balance breadth and focus, safety and speed, and humility and decisiveness.

Toward a Hybrid Logic

This essay argues for a third path: the hybrid differential. Instead of choosing between exhaustive listing and focused anchoring, the hybrid synthesizes both. It mirrors how expert clinicians actually think: they expand broadly to ensure safety, anchor pragmatically to act, narrow through testing, and re-expand when contradictions arise.

This model is not compromise but synthesis. It offers the rigor of the traditional without its paralysis and the efficiency of the reverse without its closure. It is iterative, adaptive, and teachable. Most importantly, it reflects the moral stance that diagnosis must always be provisional, always open to revision, and always guided by care.

The Structure of This Essay

In what follows, we will:

-

- Review the strengths and limitations of the traditional differential.

- Analyze the efficiency and risks of the reverse differential.

- Develop the conceptual framework of the hybrid differential.

- Apply it through clinical cases—acute chest pain, chronic cough, and the rare VEXAS syndrome.

- Discuss implications for medical education and policy.

- Debate counterarguments in a dedicated Discussion section.

- Conclude with reflections on the role of hybrid reasoning in an age of artificial intelligence.

Why This Matters Now

The stakes are high. Diagnostic error remains a leading cause of harm worldwide [8, 11]. Artificial intelligence promises to augment human reasoning, but its integration raises new epistemic challenges [10, 12]. In this context, physicians must reclaim diagnostic reasoning not as a ritual but as a living logic—one that balances thoroughness with pragmatism and uncertainty with action.

The hybrid differential is not merely a new trick of pedagogy. It is a philosophy of diagnosis. It teaches us to live with uncertainty without being paralyzed, to act decisively without being reckless, and to remain humble while exercising judgment.

In the end, diagnosis is both science and art. The hybrid differential offers a way to honor both.

Part 2. The Traditional Differential

The traditional differential diagnosis remains one of the oldest and most enduring intellectual frameworks of clinical reasoning. It is almost ritualistic: the patient presents with symptoms, the physician generates a list of possible explanations, and through history, examination, and testing, the list is progressively narrowed until one or two viable contenders remain.

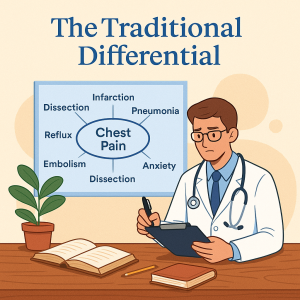

The Ritual of List-Making

Imagine a student confronted with a patient who has chest pain. The exercise begins: myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, aortic dissection, pneumonia, pericarditis, reflux, costochondritis, anxiety… The list grows. For abdominal pain, the catalog expands further—appendicitis, cholecystitis, pancreatitis, diverticulitis, mesenteric ischemia, ectopic pregnancy, irritable bowel syndrome, and beyond. The pedagogical purpose is clear: to ensure nothing is missed.

List-making becomes a badge of seriousness, a way of signaling to teachers and colleagues that one has considered the full spectrum. For students, the length of the list often substitutes for depth of reasoning. The exercise is meant to cultivate imagination: to remind the budding physician that a cough is not only bronchitis but perhaps tuberculosis, cancer, or heart failure.

Strengths of the Traditional Approach

1. Systematic Rigor: The traditional differential enforces breadth. It is a defense against premature closure. Rare diseases are not ignored simply because they are unlikely. This is especially important in high-stakes conditions like subarachnoid hemorrhage or ectopic pregnancy, where missing the diagnosis could be catastrophic.

2. Educational Value : For novices, the method is invaluable. By constructing long lists, they expand their cognitive map of disease. They learn to consider the body systemically and to integrate anatomy, physiology, and pathology. The differential becomes both a reasoning tool and a learning exercise.

3. Moral Safeguard: At its core, the traditional differential embodies a moral stance: thoroughness before certainty. It encodes the physician’s responsibility to think widely before acting narrowly.

Limitations in Contemporary Practice

But the very strengths of the traditional differential reveal its weaknesses.

1. Cognitive Overload

Cognitive psychology has long shown that working memory is limited—famously to “7 ± 2” chunks of information [3]. Constructing and holding dozens of diagnostic possibilities in mind exceeds human capacity. In practice, most clinicians cannot juggle 15–20 diagnoses at once, especially under pressure.

2. Inefficiency

In emergency medicine, exhaustive lists can be dangerous. The patient with crushing chest pain cannot wait while the physician enumerates esophageal spasm and musculoskeletal causes. Time is muscle; time is brain.

3. Over-testing

Lists beget investigations. A broad differential can drive shotgun testing, leading to overdiagnosis, incidental findings, spiraling costs, and patient harm. What began as a cognitive safeguard can paradoxically endanger the very safety it seeks to preserve.

Table 1. Strengths and Limitations of Traditional Differential Diagnosis

| Strengths | Limitations |

| Prevents missing rare conditions | Cognitively demanding, especially under pressure |

| Encourages systematic reasoning | Can lead to unnecessary investigations |

| Educationally valuable for trainees | Inefficient in emergencies |

| Broadens clinical imagination | May overwhelm novices with complexity |

The Pedagogical Debate

This tension has sparked debate in medical education. Should students still be required to “list ten causes” for every presenting complaint? Some argue this trains breadth and humility. Others contend it cultivates verbosity without judgment, producing physicians who can list but not reason.

A more nuanced critique is that the exercise, though noble in intent, does not mirror how experts actually think. Experienced clinicians rarely enumerate endless possibilities; they rapidly prioritize based on pattern recognition, epidemiology, and risk. To train novices in exhaustive listing may thus teach them a ritual disconnected from expert practice.

The Epistemic Logic

Philosophically, the traditional differential represents an inductive logic: gathering multiple possible explanations from cases and experience. It values inclusivity over selectivity, ensuring that the net is cast wide before narrowing. Induction has obvious benefits—it guards against oversight—but it is not sufficient for decisive action. Without mechanisms to prioritize, induction risks stagnation.

Clinical Illustration: Abdominal Pain

Consider the patient with right lower quadrant pain. A traditional differential might include appendicitis, ovarian torsion, ectopic pregnancy, renal colic, Crohn’s disease, diverticulitis, and more. For the novice, this is invaluable; they learn the anatomy of the abdomen and the danger of missing ectopic pregnancy. For the harried emergency physician, however, the breadth can feel unhelpful. What matters is deciding whether to operate now, order imaging, or safely discharge.

Strength in Rare Diseases

Where the traditional differential still shines is in the pursuit of rare diagnoses. Many patients with unusual conditions endure years of misdiagnosis precisely because physicians failed to generate a broad list. The rare case—Wilson’s disease, pheochromocytoma, VEXAS syndrome—often requires the imagination cultivated by the traditional method. For this reason, some argue the method must never be abandoned.

A Tool for Some Contexts, Not All

The fairest judgment is that the traditional differential is context-dependent. It is invaluable for teaching, outpatient reasoning, and rare disease consideration. It is less practical for acute care and multimorbid complexity. The danger lies in treating it as dogma rather than as one tool among many.

The Thinking Healer Reflection

The traditional differential represents medicine at its most thorough but also at its most cumbersome. It reflects a noble ethos—the refusal to overlook even the rarest condition—but risks drowning clinicians in detail. The task of modern medicine is not to abandon this tool but to integrate its rigor into a framework that can survive the demands of urgency, complexity, and uncertainty.

In this sense, the traditional differential is like the foundational grammar of clinical reasoning. One must learn the rules of grammar to master a language. But mastery is not merely reciting grammar; it is the ability to communicate fluidly, adaptively, and meaningfully. Likewise, physicians must learn the breadth of differential diagnosis, but they must also transcend it.

Part 3. The Reverse Differential

If the traditional differential is the wide net, the reverse differential is the spear. It begins not with expansiveness but with immediacy: a leading hypothesis, usually the most likely or most dangerous, is assumed provisionally true until evidence disproves it. From there, the clinician works backward, ruling out or deprioritizing other conditions.

This approach is not merely a shortcut. It represents a different epistemic posture: one of pragmatism and urgency, born from the realities of modern clinical care.

Origins in Practice

The reverse differential is not codified in the same way as the traditional; it emerged organically from practice. In the emergency department, the physician cannot list ten causes of chest pain before acting. Instead, they think: heart attack until proven otherwise. In the delivery room: postpartum hemorrhage until proven otherwise. In neurology: stroke until proven otherwise.

In each case, the logic is defensive. By assuming the worst, the physician minimizes the chance of missing a catastrophic event.

Strengths of the Reverse Approach

1. Efficiency : Clinical practice, especially acute care, demands speed. The reverse differential accelerates decision-making by focusing on the most urgent possibilities.

2. Expert Alignment : Experienced clinicians often reason in this manner, consciously or not. Pattern recognition and Bayesian intuition guide them to anchor quickly. This reflects the natural evolution of expertise: broad deliberation early in training, rapid prioritization later.

3. Pragmatism : Patients need action, not lists. Starting with the most dangerous diagnosis ensures treatment begins promptly. A patient with sepsis does not benefit from an exhaustive catalog of fever causes; they benefit from timely fluids and antibiotics.

Limitations of the Reverse Differential

1. Anchoring Bias : Psychologists Tversky and Kahneman [7] described the anchoring effect: humans tend to fixate on initial information. In medicine, this translates into overcommitment to the first hypothesis, even in the face of disconfirming evidence.

2. Premature Closure : Once an initial diagnosis is assumed, alternatives may be dismissed too early. This is among the most common contributors to diagnostic error.

3. Educational Risk: For novices, the reverse differential is hazardous. Without the foundational breadth cultivated by the traditional method, students risk narrowing too soon, failing to consider alternative explanations.

Table 2. Comparative Features of Traditional vs. Reverse Differential

| Feature | Traditional Differential | Reverse Differential |

| Starting point | Broad list of causes | Leading hypothesis |

| Cognitive style | Exhaustive, systematic | Focused, heuristic |

| Main advantage | Prevents oversight | Efficiency, speed |

| Main risk | Cognitive overload | Anchoring, premature closure |

| Best suited for | Novices, outpatients | Experts, emergencies |

The Epistemic Logic

Philosophically, the reverse differential leans on abduction—inference to the best explanation. The clinician generates a hypothesis that best fits the initial presentation, then tests its strength. Unlike induction, which seeks inclusivity, abduction seeks plausibility.

But abduction has a weakness: it is prone to overconfidence. What seems like the “best explanation” may only appear so because other possibilities have not been fully considered.

Cognitive Psychology of Anchoring

Cognitive psychology sheds light on why the reverse differential is risky. System 1 (fast, intuitive thinking) drives pattern recognition. System 2 (slow, analytical reasoning) is supposed to check it. But under stress, time pressure, or fatigue, System 2 is bypassed, leaving clinicians vulnerable to anchoring.

For example, a patient with sudden weakness may be labeled “stroke” within seconds. But if that label is not questioned, conditions like hypoglycemia, seizure, or conversion disorder may be overlooked.

Clinical Illustrations

1. Stroke Code :

A 72-year-old man with slurred speech and hemiparesis arrives in the emergency department. The reverse differential—”stroke until proven otherwise“—ensures rapid activation of CT imaging and thrombolysis pathways. This saves lives.

But it also risks error: hypoglycemia, seizure, or migraine can mimic stroke. Anchoring too tightly risks unnecessary treatment.

2. Ectopic Pregnancy:

A 30-year-old woman presents with abdominal pain and shock. “Ectopic pregnancy until proven otherwise” is a lifesaving reverse differential. Yet, if pregnancy testing is negative and anchoring persists, other causes of shock (ruptured spleen, sepsis) may be missed.

3. Sepsis :

A febrile, hypotensive patient in the ICU is assumed septic. This assumption expedites fluids and antibiotics. But if adrenal crisis or anaphylaxis is missed, antibiotics alone will not suffice.

The Pedagogical Debate

Should students be trained in reverse differentials? Advocates argue yes: it reflects real-world practice and emphasizes action. Critics warn that novices lack the judgment to know when anchoring is safe. Without breadth training, they risk catastrophic misses.

Perhaps the deeper issue is not whether to teach reverse differentials, but when. For the novice, the traditional list builds foundations. For the expert, the reverse differential mirrors natural intuition. The challenge for educators is guiding the transition.

Ethical Dimensions

The reverse differential reflects a moral stance of defensive medicine: better to overtreat than undertreat. But defensive reasoning has consequences. Anchoring every chest pain as myocardial infarction may save lives but also exposes patients to unnecessary admissions and procedures. The ethical task is to balance vigilance with restraint.

The Thinking Healer Reflection

The reverse differential is the physician’s sword: sharp, decisive, but dangerous if wielded carelessly. It reflects the realities of practice: time is finite, and danger cannot wait. Yet it also exposes the vulnerabilities of the human mind: our tendency to anchor, to close, and to assume certainty where none exists.

In many ways, the reverse differential is medicine’s paradox. It saves lives by demanding action, but it endangers lives by blinding us to alternatives. Its very efficiency is also its risk.

The challenge, then, is not to abandon the reverse differential but to integrate it into a broader cycle that tempers decisiveness with humility. This points us toward the hybrid.

Part 4. The Hybrid Differential

The traditional differential defends breadth; the reverse differential defends speed. Both are valuable, and both are dangerous. To rely on one exclusively is to court imbalance. The question is, can we design a model that preserves the strengths of both while minimizing their risks?

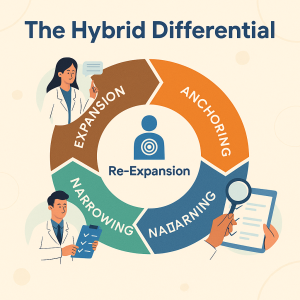

The answer is the hybrid differential. This is not compromise for the sake of middle ground. It is a structured synthesis—a cycle of reasoning that mirrors how expert clinicians actually think: expansion, anchoring, narrowing, and re-expansion.

The Cycle of Hybrid Reasoning

1. Expansion:

Begin with breadth. Generate a manageable but meaningful list of plausible diagnoses. This is not a laundry list of every conceivable cause but a curated set informed by epidemiology, physiology, and context. Expansion ensures imagination and guards against oversight.

2. Anchoring:

Identify the leading hypothesis, based on probability and danger. This is provisional anchoring, not premature closure. It provides focus for immediate testing and treatment.

3. Narrowing:

Investigate and act on the leading hypothesis. Order targeted tests. Begin treatment if indicated. Narrowing ensures efficiency and responsiveness.

4. Re-expansion:

The safeguard. If data conflict or outcomes diverge from expectations, reopen the differential deliberately. This prevents anchoring bias and premature closure. It is a cognitive forcing step: a built-in checkpoint for humility.

This four-phase cycle is iterative, not linear. Clinicians may expand, anchor, and re-expand multiple times as new evidence emerges.

Why Hybrid Reasoning Matters

The hybrid differential balances two imperatives:

• The safety imperative—don’t miss the rare but dangerous.

• The efficiency imperative—act quickly enough to save lives.

Traditional reasoning overweights safety; reverse reasoning overweights efficiency. The hybrid explicitly balances both.

Philosophical Foundations

Logic

• Induction: Broad listing of possible causes.

• Deduction: Applying general rules to the case at hand.

• Abduction: Inference to the best explanation [4].

The hybrid integrates all three, toggling between them as the cycle progresses.

Probability

The hybrid is inherently Bayesian. Probabilities are updated as new evidence emerges. Anchoring sets the prior; narrowing tests likelihood; re-expansion revises when posterior probabilities diverge.

Cognitive Psychology

The hybrid balances dual-process theory [7].

• System 1: Intuitive, heuristic, fast.

• System 2: Analytical, deliberate, slow.

The hybrid allows System 1 anchoring but forces System 2 re-expansion as a safeguard.

Table 3. Mapping Hybrid Differential to Logic and Cognitive Frameworks

| Framework | Traditional | Reverse | Hybrid |

| Logic | Induction | Abduction | Deduction + Induction + Abduction |

| Probability | Broad likelihoods | Narrow focus | Bayesian updating |

| Cognition | System 2 heavy | System 1 heavy Dual-process | Balance |

Addressing Counterarguments

1. Isn’t the hybrid just “common sense”?

Perhaps. But common sense is often tacit, unteachable. The hybrid’s value is explicitness. By naming the cycle, we transform hidden expertise into a teachable, testable model.

2. Doesn’t it add complexity?

On the contrary, it simplifies. Instead of two competing models, learners are given one cycle that incorporates both. The apparent complexity is only the articulation of what experts already do intuitively.

3. Will clinicians actually follow the cycle under pressure?

That depends on training. Just as hand hygiene became a habit through deliberate reinforcement, so too can re-expansion be trained as a reflexive safeguard.

Clinical Applications of the Hybrid

1. Chest Pain in the Emergency Department

-

- Expansion generates a shortlist: MI, dissection, PE, and pneumothorax.

-

- Anchoring prioritizes MI.

-

- Narrowing begins with ECG and troponin, initiating treatment.

-

- Re-expansion occurs if results contradict, keeping dissection alive as an alternative.

2. Chronic Cough in Outpatient Care

-

- Expansion: GERD, asthma, post-nasal drip, TB, malignancy.

-

- Anchoring: GERD (common, plausible).

-

- Narrowing: empirical reflux therapy.

-

- Re-expansion: if no improvement, revisit TB or malignancy.

3. Diagnostic Odyssey (VEXAS Syndrome)

-

- Expansion: lupus, vasculitis, autoimmune disease.

-

- Anchoring: lupus (fits symptoms).

-

- Narrowing: immunosuppression, partial response.

-

- Re-expansion: contradictions emerge. Hybrid cycle prompts genomic sequencing → diagnosis of VEXAS [9].

Safeguards Against Cognitive Bias

Hybrid reasoning is not immune to bias, but it embeds safeguards:

• Anchoring awareness: Anchoring is allowed but kept provisional.

• Premature closure check: Re-expansion forces reconsideration.

• Confirmation bias counter: Negative evidence triggers re-expansion rather than rationalization.

This transforms biases from unconscious traps into deliberate checkpoints.

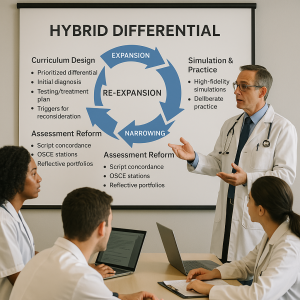

Educational Implications

For medical education, the hybrid offers a framework that unites breadth and focus.

• Curricula: Teach both list-making and pragmatic anchoring as part of one cycle.

• Assessment: Evaluate adaptability—can students re-expand when faced with contradictory data?

• Simulation: Create scenarios where initial anchors fail, forcing re-expansion.

• Bias training: Use the cycle to demonstrate cognitive forcing strategies [1].

The Ethical Dimension

The hybrid is more than a reasoning tool; it is an ethic of uncertainty.

• To expand is to honor thoroughness.

• To anchor is to honor urgency.

• To narrow is to honor action.

• To re-expand is to honor humility.

In an age where patients expect certainty and systems demand efficiency, the hybrid teaches us to live in the space between. It encodes the moral stance that diagnosis is provisional, open to revision, and guided always by care.

The Thinking Healer Reflection

The hybrid differential is not simply a new method; it is a philosophy of diagnosis. It teaches clinicians to balance imagination with pragmatism and action with humility. It reflects the reality that reasoning is not linear but cyclical, not static but iterative.

In truth, the hybrid may not be revolutionary; it may simply be descriptive of what the best clinicians already do. But in making this reasoning explicit, it becomes something greater: a framework that can be taught, studied, and refined.

The physician of the future will not merely memorize lists or anchor reflexively. They will think in cycles, toggling between breadth and focus, humility and decisiveness. They will embrace diagnosis as both science and art, logic and care.

Part 5. Clinical Case Applications

The hybrid differential must prove its worth at the bedside. The three canonical scenarios we examine here—acute chest pain, chronic cough, and the diagnostic odyssey culminating in VEXAS syndrome—illustrate how hybrid reasoning behaves in time-sensitive emergencies, in longitudinal outpatient care, and across protracted, multispecialty diagnostic journeys.

Each case is followed by a structured reflection on decisions, cognitive risks, and how the hybrid cycle (expansion → anchoring → narrowing → re-expansion) concretely changes practice.

Case 1: Acute Chest Pain—the Emergency Tightrope

Presentation

A 59-year-old man arrives by ambulance with severe, central chest pain that began while walking. He is diaphoretic, pale, mildly hypertensive, and describes the pain as pressure-like, radiating to the left arm. Past history includes hypertension and controlled type 2 diabetes. No prior coronary disease.

Hybrid reasoning stepwise.

1. Expansion (curated, prioritized):

The clinician quickly generates a short, high-yield, prioritized differential:

— Acute coronary syndrome (STEMI / NSTEMI)—highest immediate mortality/morbidity risk.

— Aortic dissection—catastrophic if missed; different management (avoid anticoagulation).

— Pulmonary embolism—treatable but time-sensitive.

— Tension pneumothorax—emergent but usually clinically obvious; consider if asymmetric breath sounds.

— Pericarditis, esophageal rupture, severe reflux, musculoskeletal pain—lower immediate mortality.

2. Anchoring (provisional): Given diaphoresis and classic radiation, anchoring on ACS is defensible as an initial working hypothesis (both common and dangerous). This anchor sets the immediate actions (ECG within 10 minutes, aspirin, oxygen if hypoxic, and talk to cardiology).

3. Narrowing (immediate actions): ECG obtained and troponin drawn. The cath lab is notified for potential PCI if the ECG shows STEMI. Meanwhile, a focused physical exam seeks dissection clues (asymmetric pulses, new murmur, tearing pain to the back) or pneumothorax signs. A bedside chest x-ray is ordered because dissection/pneumothorax must be excluded before thrombolysis.

4. Re-expansion (triggered by contradictions): If the ECG is non-diagnostic and the chest x-ray reveals a wide mediastinum, or pain moves to the back with pulse asymmetry, the clinician immediately re-expands the differential, elevating aortic dissection.

The care shift is rapid: avoid thrombolytics, and arrange emergent CT angiography and vascular surgery consultation. The initial anchor (ACS) served patient safety (prompt treatment), but re-expansion prevented catastrophic error.

Cognitive commentary

The hybrid prevented both paralysis and tunnel vision. The anchor set the lifesaving tempo; re-expansion protected against the rare but lethal alternative. Note also the timing of re-expansion: it must be rapid and protocolized—a diagnostic “timeout” when new or discordant data appear. Embedding that timeout makes re-expansion a habit, not an afterthought.

Case 2: Chronic Cough—the Long View

Presentation. A 42-year-old female teacher reports a dry cough persisting for eight weeks. She is otherwise well, a non-smoker, with no weight loss and no hemoptysis. The primary care clinic is busy; the patient wants practical solutions.

Hybrid reasoning stepwise.

1. Expansion (contextualized):

Possible causes prioritized by prevalence and risk in the local context:

— Upper airway cough syndrome (post-nasal drip)

— Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

— Asthma / cough-variant asthma

— Medication side effect (ACE inhibitor)

— Tuberculosis (regionally important if prevalence is above a certain threshold)

— Lung cancer (screen if risk factors)

— Interstitial lung disease (less likely without other features)

2. Anchoring (pragmatic): Anchor on upper airway cough syndrome / GERD given commonness and benign profile. Start pragmatic therapy: trial of intranasal steroid or proton pump inhibitor; address environmental triggers; stop ACE inhibitors if present.

3. Narrowing (monitoring and minimal testing): Arrange a follow-up at 4–6 weeks. Reserve a chest x-ray if there is no improvement or if red-flag features arise. In settings where TB prevalence is high, add targeted screening (sputum AFB / GeneXpert) earlier.

4. Re-expansion (thresholds and triggers): If cough persists or systemic signs (fever, weight loss) occur, re-expand. Add chest imaging, spirometry, and sputum testing, and consider referral. For this patient, persistence at 6 weeks prompts chest x-ray and sputum studies; imaging reveals a small upper-lobe opacity; workup confirms pulmonary TB.

Clinical reflection. The hybrid here prevents two parallel harms: over-investigation for every benign cough (if traditional differential always drives testing) and dangerous under-investigation in high-risk epidemiologic contexts (if reverse anchoring ignores TB). The explicit re-expansion trigger is the clinician’s duty: time-bound reassessment (4–6 weeks) with clear criteria for escalation.

Case 3: The Diagnostic Odyssey—VEXAS Syndrome

Presentation. A 64-year-old man with refractory fevers, relapsing chondritis, cytopenias, and inflammatory skin lesions over five years, treated variably with steroids, DMARDs, and immunosuppressive agents with inconsistent responses.

Hybrid reasoning stepwise.

1. Expansion: Over years, specialists proposed autoimmune and autoinflammatory differentials: relapsing polychondritis, systemic vasculitis, adult-onset Still’s disease, and myelodysplastic syndromes with autoimmune features.

2. Anchoring: Repeated short-term anchoring on autoimmune diagnoses led to immunosuppression cycles. Partial responses reinforced the anchor and delayed alternative investigation.

3. Narrowing: Treatments based on anchors produced intermittent improvement but increasing steroid dependence and cytopenias—clues inconsistent with classic autoimmune disease.

4. Re-expansion (crucial): The clinician re-opens the differential after recognizing the incongruence: refractory inflammation + hematologic abnormalities. This shift to re-expansion triggered targeted testing—bone marrow biopsy and next-generation genomic sequencing—revealing a somatic UBA1 mutation confirming VEXAS syndrome.

Ethical and practical note. Re-expansion in long diagnostic odysseys requires institutional support (access to advanced testing, multidisciplinary review) and clinician humility. The hybrid promotes such system-level checkpoints as periodic reconsideration of chronic cases (for example, a mandated “diagnostic review” after 12 months of unresolved disease).

Cross-Case Lessons

-

- Time sensitivity matters. In acute care, anchoring is often necessary to save time; re-expansion must be immediate when new evidence appears.

- Thresholds for re-expansion should be explicit. Time windows (e.g., 4–6 weeks for cough) or clinical triggers (asymmetric pulses in chest pain) make re-expansion operational.

- System supports increased safety. Multidisciplinary case review, accessible advanced testing, and explicit diagnostic timeouts institutionalize humility.

- Documentation of the cycle matters. Recording the anchor and the planned re-evaluation reduces bias and supports continuity of care.

Part 6. Implications for Medical Education

The hybrid differential is as much an educational framework as it is a clinical heuristic. It bridges the long-standing gap between what novices are taught (comprehensive lists) and what they observe in practice (experts’ focused anchors). Implementing the hybrid into curricula, assessment, and faculty development offers concrete benefits.

Curriculum Design: From Lists to Cycles

Learning objectives for a hybrid curriculum might include:

• The ability to generate a prioritized, context-sensitive differential (expansion).

• Judicious selection of an initial working diagnosis and rationale (anchoring).

• Creating a time-bounded plan for testing/treatment (narrowing).

• Setting explicit triggers and timelines for reconsideration (re-expansion).

Curricula should incorporate case libraries with explicit annotations showing how expansion and re-expansion occurred. Faculty should model the cycle in rounds, articulating anchors and rechecking plans.

Simulation and Deliberate Practice

Simulation is ideal for rehearsing re-expansion. Scenarios can be constructed where the initial anchor fails:

• High-fidelity chest pain simulation: Initial ECG is non-diagnostic; after initial treatments, the patient develops mediastinal widening; simulation forces the learner to re-expand and order CT angiography.

• Chronic cough OSCE: Student prescribes PPI; standardized patient returns at 6 weeks with no improvement; the station assesses whether the student re-expands and orders chest imaging.

Deliberate practice emphasizes both speed (anchoring and narrow action) and metacognition (recognizing disconfirming evidence).

Assessment Reform

Traditional exams reward long differential lists. Hybrid-oriented assessment should measure adaptability:

• Script concordance tests (SCTs): Present scenarios with changing data; measure whether students update probabilities appropriately.

• OSCE stations with twist endings: Require students to revise initial hypotheses.

• Reflective portfolios: Ask learners to document cases where they re-expanded their differential and what prompted it.

Grading rubrics should reward documented plans for re-evaluation (clear criteria and timelines), not only the number of diagnoses listed.

Faculty Development

Faculty must be trained to teach the hybrid cycle explicitly. Teaching points include:

• Modeling provisional anchoring with explicit re-evaluation plans.

• Demonstrating cognitive forcing techniques (deliberate questioning of initial assumptions).

• Creating a culture where admitting uncertainty and revising diagnoses is normalized.

Faculty evaluation metrics could include how often attendings verbalize anchors and re-evaluation plans during rounds.

Systems and Institutional Supports in Training

Embedding hybrid reasoning into training requires systems:

• Diagnostic review boards for protracted cases.

• EHR prompts that remind clinicians of pending re-evaluation dates.

• Access to decision support that provides broad expansions (AI lists) while prompting human anchors and rechecks.

Part 7. Future Directions

The hybrid differential sets an agenda for research, policy, and integration with new technologies. Below are priority avenues and practical considerations.

Human-AI Collaboration

AI can augment expansion by generating exhaustive, data-driven differentials and suggesting probabilities. But without human framing, AI lists can be overwhelming or misleading.

Principles for collaboration:

-

- AI for expansion; humans for anchoring. Let machines enumerate and rank possibilities; humans decide which candidate to anchor on given values, context, and risk tolerance.

- Explainability and trust. AI outputs must be interpretable—clinicians need to know why a diagnosis was suggested (feature attribution).

- AI-triggered re-expansion. If a patient trajectory diverges from model predictions, AI can prompt a re-evaluation (an automated “diagnostic safety alert”).

Research should test whether AI-augmented hybrid cycles reduce time to correct diagnosis and cognitive load versus human-only or AI-only strategies.

Diagnostic Safety and Quality Metrics

The hybrid differential suggests measurable process metrics:

• Re-expansion rate: proportion of cases where the clinician formally reopens the differential after a pre-specified trigger.

• Time-to-re-expansion: interval from discordant evidence to documented re-evaluation.

• Diagnostic closure documentation: explicit notes indicating when a diagnosis is considered settled and why.

These process measures can complement outcome measures (diagnostic accuracy, morbidity, litigation) and support quality improvement.

Global Health and Contextualization

The hybrid is content-agnostic but context-sensitive. Implementation requires local calibration:

• High-prevalence settings (e.g., TB, malaria): expansion lists must keep these diseases prominent; anchoring should account for endemic risks.

• Resource-limited settings: anchoring may prioritize treatable, high-prevalence conditions; re-expansion may require different thresholds due to limited diagnostics.

Research across diverse settings will clarify how to adapt thresholds and re-expansion triggers.

Research Priorities

Key studies to validate the hybrid:

-

- Randomized trials comparing hybrid-trained clinicians vs standard training on diagnostic accuracy and time metrics in simulated emergencies.

- Implementation studies embedding re-expansion prompts into EHRs and measuring clinician behavior and outcomes.

- Cognitive load research using validated scales to determine whether hybrid strategies reduce mental effort compared to exhaustive lists.

- AI integration trials testing human-AI teaming where AI provides expansion and clinicians manage anchors and rechecks.

Funding agencies and academic centers should prioritize these mixed-methods studies.

Conclusion

Diagnosis sits at the crossroads of knowledge, judgment, and care. The traditional differential and the reverse differential each capture essential elements of responsible practice: breadth and speed. But neither alone is sufficient. The hybrid differential—an explicit cycle of expansion, anchoring, narrowing, and re-expansion—synthesizes these elements into a single, teachable, and improvable framework.

The hybrid respects the limits of human cognition. It invites humility by formalizing re-expansion. It supports action by endorsing provisional anchors. It harmonizes with emerging technologies: AI can supply exhaustive expansion; clinicians remain responsible for value-laden anchoring and timely re-evaluation.

Most importantly, the hybrid is ethical: it encodes an approach to uncertainty that balances patient safety and efficient care. It turns tacit expertise into explicit pedagogy, opens new possibilities for research, and provides a scaffold for human-machine collaboration.

Discussion

In this final, argumentative section I address likely critiques, ethical tensions, and practical limits.

“Not New”—Why Codification Matters

Skeptics will say the hybrid is merely what good clinicians already do. That may be true. But tacit practice is not the same as transmissible pedagogy. Codifying the cycle allows deliberate teaching, objective study, and systemization. Without naming steps like re-expansion and anchoring documentation, we cannot measure, improve, or scale good practice.

Bias and Human Fallibility

No model immunizes us against cognitive bias. Anchoring remains powerful. What the hybrid offers is a procedural counterweight: re-expansion as a required, time-bound checkpoint reduces the chance that anchoring ossifies.

But systems must support the process: diagnostic review, EHR prompts, and incentives for revisiting diagnoses. Otherwise, re-expansion remains aspirational.

Ethical Tradeoffs

The hybrid asks clinicians to balance two moral claims: the obligation to act to prevent immediate harm and the obligation to avoid harm from incorrect action (over-treatment, inappropriate procedures). The model offers a procedural ethic: act provisionally but plan for revision. It demands communicating provisionality to patients: informed consent includes acknowledging diagnostic uncertainty and planning re-evaluation.

Limitations

• Resource constraints may limit re-expansion options (imaging, genomic tests). The hybrid must be adapted pragmatically.

• Cultural barriers in some clinical environments discourage admitting uncertainty. Faculty development and culture change are essential.

• Measurement difficulties: counting re-expansions and linking them to outcomes requires careful methodology.

Practical Implementation

Start small: pilot hybrid training in one residency program with simulation and EHR prompts. Measure process outcomes (documentation of re-evaluation plans) and clinician feedback. Iterate.

Closing Thought—The Physician as Navigator

In an era of rapid data accumulation and algorithmic power, the physician’s role is shifting from sole pattern-matcher to navigator of uncertainty. The hybrid differential is a navigation protocol: use broad maps (expansion) and focused compasses (anchors), move swiftly (narrowing), and be willing to change course when the landscape changes (re-expansion).

That navigation—the balance of courage and humility—remains the heart of clinical judgment.

References

-

- Croskerry P. Cognitive forcing strategies in clinical decision-making. Ann Emerg Med. 2003.

- Kassirer JP. Teaching clinical reasoning: case-based and coached. Acad Med. 2010.

- Norman G. Research in clinical reasoning: past history and current trends. Med Educ. 2005.

- Peirce CS. Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce. Harvard University Press.

- Rawls, J. A Theory of Justice. 1971.

- Sen, A. Development as Freedom. 1999.

- Tversky A, Kahneman D. Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. Science. 1974.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Improving Diagnosis in Health Care. 2015.

- Scully EP, et al. VEXAS syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2020.

- Topol EJ. High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat Med. 2019.

- Graber ML, et al. The science of diagnostic error. Diagnosis. 2018.

- Shortliffe EH, Sepúlveda MJ. Artificial intelligence in decision support: challenges for clinical adoption. JAMA. 2018.

Blog Summary

This flagship essay introduces the hybrid differential—a four-step diagnostic cycle (expansion → anchoring → narrowing → re-expansion) that integrates the safety of traditional differential diagnosis with the efficiency of reverse-anchoring strategies. Drawing on philosophy (abduction, Bayesian logic), cognitive science (dual-process theory), and clinical cases (acute chest pain, chronic cough, VEXAS), the hybrid model offers a teachable framework for improving diagnostic accuracy, reducing cognitive error, and safely integrating AI decision support. The hybrid reframes diagnosis as iterative, provisional, and ethically accountable—the physician as navigator of uncertainty.

Leave a Reply